FLAG EAGLE, MODEL 1815, FIRST EMPIRE.

Sold out

FLAG EAGLE, MODEL 1815, FIRST EMPIRE.

The eagle is shown in right profile, with a slightly raised frontal posture, a short hooked and closed beak. The wings are semi-spread, slightly lower than on the Model 1804, feathers are spread out, and the tips point downwards, with the left wing distinctly lower than the spindle. It stands on its left claw, leaning on the thin terrace of the caisson (absent), while the right claw holds the Jupiter's spindle without lightning bolts, thicker and placed at a greater angle than on the Model 1804.

Height at the front of the eagle: 20.8 cm.

Height at the back: 21.9 cm.

Width: 22.5 cm.

Height of the right wing of the eagle: 15.9 cm (left wing when examining the eagle from the front).

Height of the left wing of the eagle: 15.9 cm (right wing when examining the eagle from the front).

Length of the spindle: 14.2 cm.

Spindle diameter: 2.2 cm.

Total weight: 1451 g.

Markings: No visible external marks.

France.

First Empire period (April - May 1815).

Good state of conservation. The eagle has largely lost its gilding. Slight indentation on the left side of the eagle's chest and a less visible one at the back of the right wing. On the outer edges at the level of the wings and head, seven small notches are present, most likely made at the time due to sword blows; two other similar blows are present on the spindle. Some usual imperfections in the soldering from the front to the back part of the eagle.

PROVENANCE:

Eagle from the former SAINT-AUBIN collection, transferred on February 4, 1936 to a French collector, where it remained in a collection until 2012.

PROVENANCE:

Former Wurtz-Pees collection, then Saint-Aubin, and private collection.

Mister Marcel Saint-Aubin, was a collector who became an antiquarian between the two World Wars. To my knowledge, no biography or article has ever been published about this individual, who is nevertheless known by collectors and is often cited in the provenance of historically significant objects of high quality. I will now open my archives to better introduce this great connoisseur:

"Mobilized during World War I along with his brother in the infantry, the latter was killed at Verdun. Both shared the same taste for military memorabilia; both drew and published their drawings in the magazine 'La Giberne' before 1914.

After the war, he established himself as an antiquarian. In 1926, he lived at 108 rue de Ménilmontant (Paris 20th), far from the preferred districts of antiquarians. His choice was guided by the specialty that attracted him: military curiosities. His interest in this specialty was sparked by his first find: an officer's saber from the Consulate, his first fine saber; he called it his 'lucky charm' and always kept it.

The profession of antiquarian allowed Saint-Aubin to see and possess these much-appreciated objects for a while. A discerning connoisseur, he never made mistakes, and his clients benefited from his expertise. A passionate researcher, everything he discovered in his life was surprisingly varied. Silent and modest, he had an art and manner that left an indelible memory among the collectors who knew him.

Like most military objects dealers of that time, Marcel Saint-Aubin did not have a store. He received visitors in his apartment, where few objects were displayed temporarily. Generally, like Paul Jean, he would fetch the objects he wanted to sell from the neighboring room and present them often without saying a word, with a slight smile, or if the presented object was truly exceptional, he would simply say in a low voice, 'It's top-notch...'.

In June 1940, during the occupation, he left for Guingamp. He returned to Paris and resettled at the end of 1951 in the house he had acquired at 16 rue Henri Pape, in the 13th arrondissement, once again far from the antique districts.

His love for the objects he parted with extended to the care he took in their packaging. Very skilled with his hands, he perfectly protected even the most modest piece.

Marcel Saint-Aubin passed away at the age of 83, taking with him the esteem of all who knew him, leaving behind a unanimously held memory of a man with great moral values."

RARITY:

We exceptionally qualify this object as "rare," as genuine First Empire items are naturally scarce. Regarding this type of object, a Model 1815 eagle is particularly rare.

Based on Pierre Charrié's work "Flags and Standards of the Revolution and the Empire," and complemented by our visits to major collections or public collections, here is an inventory of the 1815 eagles; currently, approximately 76 eagles are known:

45th Infantry at the Museum of Edimburg.

52nd Infantry seen in 1823 by a French officer, lost since that date.

86th Infantry (caisson redone under the Second Empire) at the Geneva Museum.

105th Infantry at the National Army Museum.

6th Light Cavalry Chasseurs in a private collection.

2nd Hussars at the Army Museum in Paris.

2nd Foot Grenadier of the Imperial Guard given to Marshal Oudinot, Duke of Reggio, by King Louis XVIII in 1815.

National Guard, 67 eagles and 68 flags were given by King Louis XVIII to Wellington in Paris after the Battle of Waterloo; they are currently still kept at Aspley House in London (the Duke of Wellington's residence turned museum).

Eagle without a caisson, found in the Seine in a private collection.

The eagle presented today.

HISTORICAL INFORMATION:

FLAG EAGLES OF THE FIRST EMPIRE

After the proclamation of the Empire on May 18, 1804, Napoleon chose the eagle as the new emblem of the Nation. It was the painter Jean-Baptiste Isabey who designed the French Eagle that appeared on the imperial seal.

On July 27, 1804, Napoleon decided that a gilded bronze eagle would be placed at the top of the staff of the new flags, standards, and tricolor flags. He specified that it would be the eagle, rather than the silk, that would essentially constitute the emblem. Flags and standards were now called Eagles. It was planned that each battalion of infantry troops and each squadron of cavalry troops would receive an Eagle, totaling more than 1,100 Eagles, including the 38 Eagles intended for ship flags. The caisson originally displayed the regiment's numeral on both faces, later only on the front face.

The Emperor insisted on personally handing over the Eagles: "Soldiers, here are your flags! These eagles will always serve as your rallying point; they will be wherever your emperor deems their presence necessary for the defense of his throne and his people. You swear to sacrifice your life to defend them, and to keep them constantly on the path of victory through your courage." The first distribution, at the Champ de Mars on December 5, 1804, was the most lavish and remains the most famous, immortalized by Jacques-Louis David's painting. The imperial decree of February 18, 1808, reducing the number of Eagles to one per regiment, returned the excess Eagles to the War Administration, and some were redistributed to replace those lost in battle. Throughout his reign, Napoleon handed out Eagles at military parades in the Tuileries courtyard. Article 1 of the imperial decree of December 25, 1811, stipulated: "No unit can bear the French eagle as its ensign unless it has received it from our hands and has sworn allegiance." Nevertheless, some Eagles were delivered by the Minister of War, and a few others by a general officer to distant regiments during campaigns.

In 1810-1811, a new lightweight Eagle was distributed to new regiments or to authorized older regiments to replace their lost Eagles. Made by Thomire based on the Model 1804, this stamped Eagle had a reduced weight of over half, but with less attention to detail. When the Eagles were ordered for the National Guard on March 28, 1815, Thomire invoiced an Eagle for 85 francs.

After his return from Elba, the Model 1815 Eagle was designed and manufactured, and the distributions on June 1 and 4, 1815, were highly solemn.

The Eagle had to march with the main body of the regiment where the Colonel was stationed and was fiercely defended by the ensign-bearers and the regiment. At Waterloo, General Pelet, along with a handful of men and the ensign-bearer of the Old Guard Chasseurs, rallied his troops by shouting, "To me, Old Guard Chasseurs, let's save the Eagle or die near it." In defeat, the Eagle was concealed by prisoner soldiers, buried, or destroyed to avoid capture by the enemy.

The eagle is shown in right profile, with a slightly raised frontal posture, a short hooked and closed beak. The wings are semi-spread, slightly lower than on the Model 1804, feathers are spread out, and the tips point downwards, with the left wing distinctly lower than the spindle. It stands on its left claw, leaning on the thin terrace of the caisson (absent), while the right claw holds the Jupiter's spindle without lightning bolts, thicker and placed at a greater angle than on the Model 1804.

Height at the front of the eagle: 20.8 cm.

Height at the back: 21.9 cm.

Width: 22.5 cm.

Height of the right wing of the eagle: 15.9 cm (left wing when examining the eagle from the front).

Height of the left wing of the eagle: 15.9 cm (right wing when examining the eagle from the front).

Length of the spindle: 14.2 cm.

Spindle diameter: 2.2 cm.

Total weight: 1451 g.

Markings: No visible external marks.

France.

First Empire period (April - May 1815).

Good state of conservation. The eagle has largely lost its gilding. Slight indentation on the left side of the eagle's chest and a less visible one at the back of the right wing. On the outer edges at the level of the wings and head, seven small notches are present, most likely made at the time due to sword blows; two other similar blows are present on the spindle. Some usual imperfections in the soldering from the front to the back part of the eagle.

PROVENANCE:

Eagle from the former SAINT-AUBIN collection, transferred on February 4, 1936 to a French collector, where it remained in a collection until 2012.

PROVENANCE:

Former Wurtz-Pees collection, then Saint-Aubin, and private collection.

Mister Marcel Saint-Aubin, was a collector who became an antiquarian between the two World Wars. To my knowledge, no biography or article has ever been published about this individual, who is nevertheless known by collectors and is often cited in the provenance of historically significant objects of high quality. I will now open my archives to better introduce this great connoisseur:

"Mobilized during World War I along with his brother in the infantry, the latter was killed at Verdun. Both shared the same taste for military memorabilia; both drew and published their drawings in the magazine 'La Giberne' before 1914.

After the war, he established himself as an antiquarian. In 1926, he lived at 108 rue de Ménilmontant (Paris 20th), far from the preferred districts of antiquarians. His choice was guided by the specialty that attracted him: military curiosities. His interest in this specialty was sparked by his first find: an officer's saber from the Consulate, his first fine saber; he called it his 'lucky charm' and always kept it.

The profession of antiquarian allowed Saint-Aubin to see and possess these much-appreciated objects for a while. A discerning connoisseur, he never made mistakes, and his clients benefited from his expertise. A passionate researcher, everything he discovered in his life was surprisingly varied. Silent and modest, he had an art and manner that left an indelible memory among the collectors who knew him.

Like most military objects dealers of that time, Marcel Saint-Aubin did not have a store. He received visitors in his apartment, where few objects were displayed temporarily. Generally, like Paul Jean, he would fetch the objects he wanted to sell from the neighboring room and present them often without saying a word, with a slight smile, or if the presented object was truly exceptional, he would simply say in a low voice, 'It's top-notch...'.

In June 1940, during the occupation, he left for Guingamp. He returned to Paris and resettled at the end of 1951 in the house he had acquired at 16 rue Henri Pape, in the 13th arrondissement, once again far from the antique districts.

His love for the objects he parted with extended to the care he took in their packaging. Very skilled with his hands, he perfectly protected even the most modest piece.

Marcel Saint-Aubin passed away at the age of 83, taking with him the esteem of all who knew him, leaving behind a unanimously held memory of a man with great moral values."

RARITY:

We exceptionally qualify this object as "rare," as genuine First Empire items are naturally scarce. Regarding this type of object, a Model 1815 eagle is particularly rare.

Based on Pierre Charrié's work "Flags and Standards of the Revolution and the Empire," and complemented by our visits to major collections or public collections, here is an inventory of the 1815 eagles; currently, approximately 76 eagles are known:

45th Infantry at the Museum of Edimburg.

52nd Infantry seen in 1823 by a French officer, lost since that date.

86th Infantry (caisson redone under the Second Empire) at the Geneva Museum.

105th Infantry at the National Army Museum.

6th Light Cavalry Chasseurs in a private collection.

2nd Hussars at the Army Museum in Paris.

2nd Foot Grenadier of the Imperial Guard given to Marshal Oudinot, Duke of Reggio, by King Louis XVIII in 1815.

National Guard, 67 eagles and 68 flags were given by King Louis XVIII to Wellington in Paris after the Battle of Waterloo; they are currently still kept at Aspley House in London (the Duke of Wellington's residence turned museum).

Eagle without a caisson, found in the Seine in a private collection.

The eagle presented today.

HISTORICAL INFORMATION:

FLAG EAGLES OF THE FIRST EMPIRE

After the proclamation of the Empire on May 18, 1804, Napoleon chose the eagle as the new emblem of the Nation. It was the painter Jean-Baptiste Isabey who designed the French Eagle that appeared on the imperial seal.

On July 27, 1804, Napoleon decided that a gilded bronze eagle would be placed at the top of the staff of the new flags, standards, and tricolor flags. He specified that it would be the eagle, rather than the silk, that would essentially constitute the emblem. Flags and standards were now called Eagles. It was planned that each battalion of infantry troops and each squadron of cavalry troops would receive an Eagle, totaling more than 1,100 Eagles, including the 38 Eagles intended for ship flags. The caisson originally displayed the regiment's numeral on both faces, later only on the front face.

The Emperor insisted on personally handing over the Eagles: "Soldiers, here are your flags! These eagles will always serve as your rallying point; they will be wherever your emperor deems their presence necessary for the defense of his throne and his people. You swear to sacrifice your life to defend them, and to keep them constantly on the path of victory through your courage." The first distribution, at the Champ de Mars on December 5, 1804, was the most lavish and remains the most famous, immortalized by Jacques-Louis David's painting. The imperial decree of February 18, 1808, reducing the number of Eagles to one per regiment, returned the excess Eagles to the War Administration, and some were redistributed to replace those lost in battle. Throughout his reign, Napoleon handed out Eagles at military parades in the Tuileries courtyard. Article 1 of the imperial decree of December 25, 1811, stipulated: "No unit can bear the French eagle as its ensign unless it has received it from our hands and has sworn allegiance." Nevertheless, some Eagles were delivered by the Minister of War, and a few others by a general officer to distant regiments during campaigns.

In 1810-1811, a new lightweight Eagle was distributed to new regiments or to authorized older regiments to replace their lost Eagles. Made by Thomire based on the Model 1804, this stamped Eagle had a reduced weight of over half, but with less attention to detail. When the Eagles were ordered for the National Guard on March 28, 1815, Thomire invoiced an Eagle for 85 francs.

After his return from Elba, the Model 1815 Eagle was designed and manufactured, and the distributions on June 1 and 4, 1815, were highly solemn.

The Eagle had to march with the main body of the regiment where the Colonel was stationed and was fiercely defended by the ensign-bearers and the regiment. At Waterloo, General Pelet, along with a handful of men and the ensign-bearer of the Old Guard Chasseurs, rallied his troops by shouting, "To me, Old Guard Chasseurs, let's save the Eagle or die near it." In defeat, the Eagle was concealed by prisoner soldiers, buried, or destroyed to avoid capture by the enemy.

Reference :

3293

Next update Friday, February 13 at 13:30 PM

FOR ALL PURCHASES, PAYMENT IN MULTIPLE CHECKS POSSIBLE

bertrand.malvaux@wanadoo.fr 06 07 75 74 63

SHIPPING COSTS

Shipping costs are calculated only once per order for one or more items, all shipments are sent via registered mail, as this is the only way to have proof of dispatch and receipt.

For parcels whose value cannot be insured by the Post, shipments are entrusted to DHL or Fedex with real value insured, the service is of high quality but the cost is higher.

RETURN POLICY

Items can be returned within 8 days of receipt. They must be returned by registered mail at the sender's expense, in their original packaging, and in their original condition.

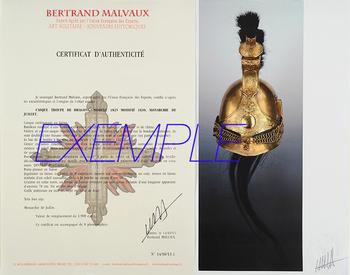

AUTHENTICITY

The selection of items offered on this site allows me to guarantee the authenticity of each piece described here, all items offered are guaranteed to be period and authentic, unless otherwise noted or restricted in the description.

An authenticity certificate of the item including the description published on the site, the period, the sale price, accompanied by one or more color photographs is automatically provided for any item priced over 130 euros. Below this price, each certificate is charged 5 euros.

Only items sold by me are subject to an authenticity certificate, I do not provide any expert reports for items sold by third parties (colleagues or collectors).

FOR ALL PURCHASES, PAYMENT IN MULTIPLE CHECKS POSSIBLE

bertrand.malvaux@wanadoo.fr 06 07 75 74 63

An authenticity certificate of the item including the description published on the site, the period, the sale price, accompanied by one or more color photographs is automatically provided for any item priced over 130 euros. Below this price, each certificate is charged 5 euros.

Only items sold by me are subject to an authenticity certificate, I do not provide any expert reports for items sold by third parties (colleagues or collectors).